The Mattaponi River, upstream of its confluence with the South River. Antepenultimate, CC BY-SA 4.0. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mattaponi_River_20170218.jpg

Everyone knows the name Pocahontas, but her story is usually remembered in pieces. Most people will guess that Pocahontas saved John Smith from being executed by her father and that they were married, bringing peace between the English and the Powhatan Nation. This is the residue of a more detailed myth, that Pocahontas recognized the superiority of the English society and enthusiastically chose to marry an Englishman, convert to Christianity, and renounce her own people. This legend was created to glorify one culture, and justify the conquest of another.

As the English colonies that would become the United States grew, they created laws that helped them control Native, Black, and mixed-race people. These laws excluded them from voting, from juries, from owning property, and above all, from socializing with or marrying White people. It is darkly ironic then that the descendents of John Rolfe would long celebrate their relation to Pocahontas, the “Indian Princess.” As wealthy Virginia elites, they were immune to the stigma of Indian blood that marked so many in their community as outsiders and subhumans.

The true story of Matoaka is short and tragic.

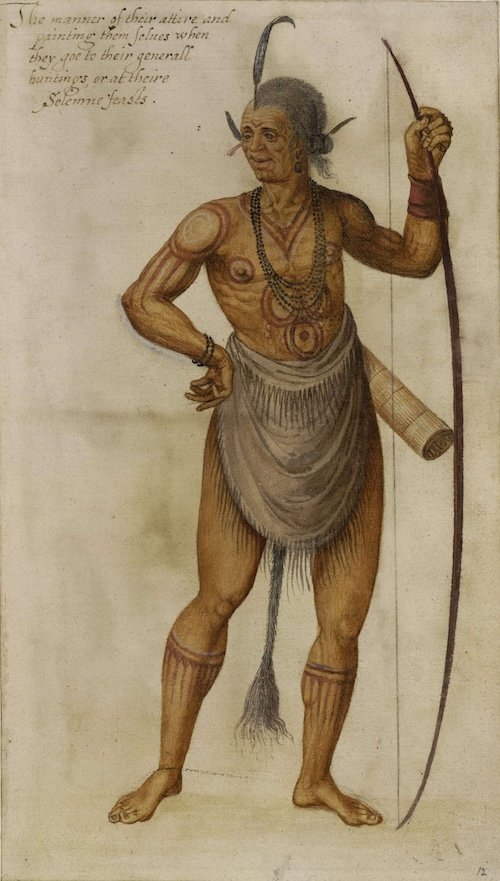

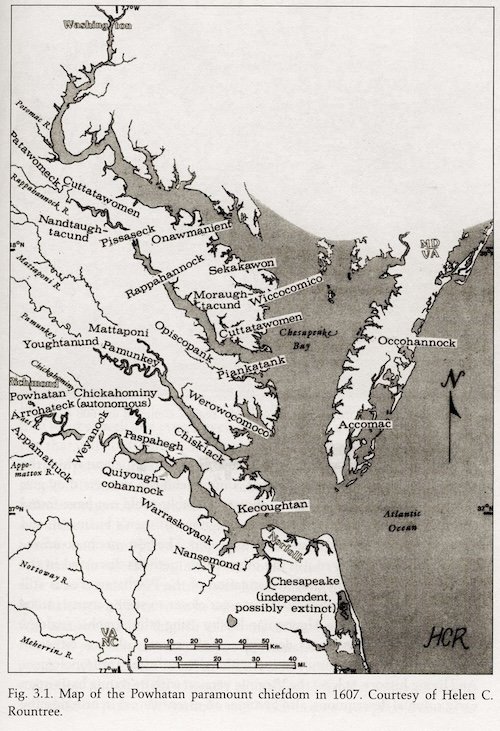

Matoaka’s father, Wahunsenaca, made Captain John Smith a werowance in an attempt to assimilate the English into the Powhatan Nation. She was a frequent visitor to Jamestown when she was between 10-13, accompanying delegations that brought food to the colonists. She learned English from Smith and others, probably most from the English boys left with her people to learn their language and customs. As relations between the Powhatan and the English soured, she became a target for abduction. She married a young Patawomeck man named Kakoum and lived with his people in the north of Tsenacomoco. They had a son together. In 1613 she was kidnapped by Captain Samuel Argall.

Argall coerced the Patawomeck werowance into helping him and demanded as her ransom, the return of all English weapons and prisoners from Wahunsenaca, as well as large amounts of corn to feed the fort. Though Wahunsenaca agreed to these terms, the colony’s governor, Thomas Gates found excuses to claim it was not paid and kept Matoaka prisoner. After an initial captivity in Jamestown, Matoaka was sent to Henrico where the Reverend Alex Whitaker instructed her in Christianity and urged her to convert. The tobacco planter John Rolfe assisted Whitaker with teaching her English here. Rolfe claimed to have fallen in love with Matoaka and proposed to marry her. The colony’s governors forwarded his proposal to her father, while also threatening war with him if their demands for a regular supply of food were not met. Wahunsenaca consented to the marriage, hoping to secure his daughter’s safety and a beneficial peace with the English. Matoaka and John Rolfe had a son named Thomas. Most sources claim the child was Rolfe’s, conceived soon after their marriage. However the Mattaponi Oral History records that Matoaka revealed to her sister she was raped soon after being taken hostage. The Mattaponi therefore suspect that Thomas Rolfe was not John Rolfe’s biological son, and that his marriage to Matoaka may have been orchestrated by the colony’s governors.

Once the tentative peace had been agreed to, Matoaka converted to Christianity, took the name Rebecca, and married Rolfe. Hostilities continued to erupt. Colonists raided for food in lean times, and took land Native people had cleared for crops along the riverbanks as opportunities arose. Those who strayed from the forts were often robbed and murdered. Outright war, though, was averted.

In 1616, the Virginia Company sent Matoaka and Rolfe to England to publicize the colony and present an image of peaceful relations with “civilizable” Indians. Matoaka and her entourage became minor celebrities in London. She was entertained in the homes of English elites, met King James I and Queen Anne, attended a Royal Masque, and had a last meeting with Captain John Smith, who she scolded for breaking the bond he had entered into with her Father in 1607 when he was made werowance of the English.

As the party prepared to set sail back to Virginia, Matoaka became ill. Most sources note only that Matoaka began feeling ill, some say it was only her, others that all of the Powhatans were suffering from sickness. The Mattaponi Oral History records that Matoaka told her sister that she believed she was poisoned while dining with Rolfe and Captain Argall, and that she died on the ship. Most sources claim she died at an inn in the town of Gravesend, where the ship stopped. All agree she was buried at St. George’s church nearby.

It is tempting, especially this far removed from the events, to rewrite Matoaka’s story yet again. To cast her as a shrewd victim of circumstance, who attempted to sacrifice herself to bring peace between her people and an invading tribe. However, no one can know Matoaka’s thoughts, or her motivations. The little documentation we have of her life comes from other, mostly European, sources. Filling the empty spaces in that story with drama and speculation without acknowledging the lies and uncertainties does her memory further disservice.

Camille Townsend ends her book, “Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma,” with a sobering thesis that I believe avoids the common overreaches of most histories:

“The destruction of Virginia’s Indian tribes was not a question of miscommunication and missed opportunities. White settlers wanted the Indians’ land and had the strength to take it; the Indians could not live without their land. It is unfair to imply that somehow Pocahontas, or Queen Cockacoeske, or others like them could have done more, could have played their cards differently, and so have saved their people. The gambling game they were forced to play was a dangerous one, and they had one hand, even two, tied behind their backs at all times. It is important to do them the honor of believing that they did their best. They all made decisions as well as they could, managing in what were often nearly unbearable situations. There is nothing they could have done that would have dramatically changed the outcome: a new nation was going to be built on their people’s destruction– a destruction that would be either partial or complete. They did not fail. On the contrary, theirs is a story of heroism as it exists in the real world, not in epic tales. Their dwindling people did survive, against all odds.”

Sources:

Images of a Legend - PBS

Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend- National Parks Service

Matoaka’s Story

Bibliography

Custalow, Linwood “Little Bear” and Angela L. Daniel “Silver Star.” The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Downloadable ebook. Chicago: Fulcrum Publishing, 2007.

Downs, Kristina. “Mirrored Archetypes: The Contrasting Cultural Roles of La Malinche and Pocahontas.” Western Folklore 67, no. 4 (2008): 397–414.

Freund, Virginia, and Louis B. Wright. The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania (1612), by William Strachey, Gent. Hakluyt Society, Second Series, v. 103. London: Taylor and Francis, 2011.

Gilliam, Charles Edgar. “His Dearest Daughter’s Names.” The William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 21, no. 3 (1941): 239–42.

Hamor, Ralph, Thomas Harriot, George Percy, and John Rolf. Virginia; Four Personal Narratives. Research Library of Colonial Americana. New York: Arno Press, 1972.

Heuvel, Lisa. “The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. By Linwood ‘Little Bear’ Custalow and Angela L. Daniel ‘Silver Star.’” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 31, no. 3 (June 1, 2007). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8pq8q3m8.

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. Pocahontas and the English Boys: Caught between Cultures in Early Virginia. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl, and Karen O. Kupperman. Captain John Smith: A Select Edition of His Writings. Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia Ser. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

LeMaster, Michelle. “Pocahontas: (De)Constructing an American Myth.” Edited by Camilla Townsend, Helen C. Rountree, Paula Gunn Allen, and David A. Price. The William and Mary Quarterly 62, no. 4 (2005): 774–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/3491451.

Lopenzina, Drew. “The Wedding of Pocahontas and John Rolfe: How to Keep the Thrill Alive after Four Hundred Years of Marriage.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 26, no. 4 (2014): 59–77. https://doi.org/10.5250/studamerindilite.26.4.0059.

Rountree, Helen C. “Powhatan Indian Women: The People Captain John Smith Barely Saw.” Ethnohistory 45, no. 1 (1998): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/483170.

Strachey, William, Silvester Jourdain, Louis B. Wright, and Alden T. Vaughan. A Voyage to Virginia in 1609: Two Narratives. 2nd ed. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013.

“The True Story of Pocahontas-C-SPAN.Org.” Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.c-span.org/video/?202747-2/the-true-story-pocahontas.

Townsend, Camilla. “Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma.” New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Wood, Karenne. “Prisoners of History: Pocahontas, Mary Jemison, and the Poetics of an American Myth.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 28, no. 1 (2016): 73–82. https://doi.org/10.5250/studamerindilite.28.1.0073.

Working, Lauren. Review of Review of Pocahontas and the English Boys: Caught between Cultures in Early Virginia, by Karen Ordahl Kupperman. The William and Mary Quarterly 77, no. 1 (2020): 138–43.