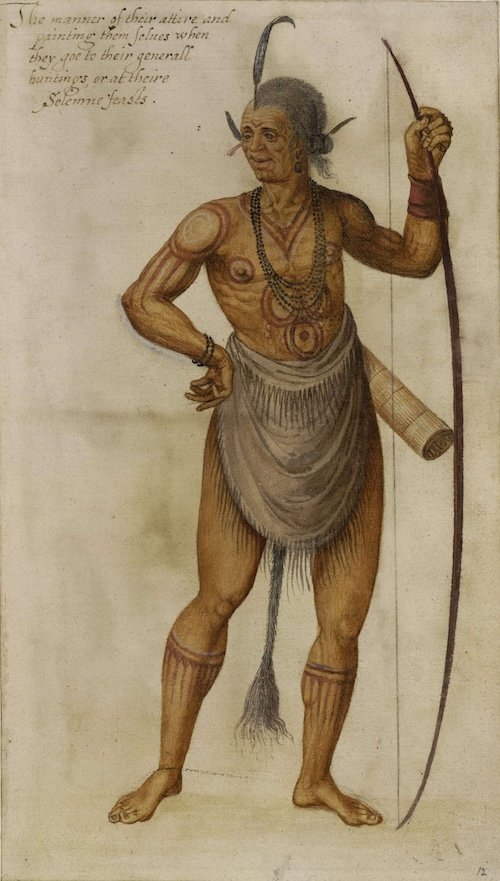

“The manner of their attire and painting them selves when they goe to their generall huntings or at theire solemne feasts.” Watercolor. John White. 1585. Public Domain.

John Rolfe returned to Jamestown a widower for the second time. He soon remarried and became a leading figure in the colony. He is one of the sources who wrote about the first enslaved Africans brought to an English colony in North America in 1619. They were seized from a Portuguese slave ship by Dutch privateers and sold as indentured servants in Jamestown. Rolfe died in 1622 but the cause is unknown. It is possible he was killed in what became known as the “Indian Massacre” of the same year, but that has never been verified.

Wahunsenca abdicated the role of Paramount Werowance soon after learning of Matoaka’s death. The Mattaponi Oral History records that her abduction had thrown him into a deep depression that left him increasingly indecisive about how to proceed against the English. He could no longer lead and died in April of 1618, roughly a year after his daughter. His brother Opitcham became the official Paramount Werowance, but Opechancanough (O-pee-ken’-can-oo), the Powhatan War Werowance, began to take a larger role in the Powhatan Nation’s governance. He maintained the official peace with the English, though disputes over land and trade, as well as violent incidents, continued. But secretly, Opechancanough was planning a concerted assault on nearly all of the colonies. On March 22nd, 1622, multiple parties visited English settlements and forts as usual, but at an appointed time, began executing English men, women, and children. Jamestown itself was secured in time to stave off a direct assault thanks to Native people, some Powhatans, some of other tribes, who warned them just in time.

The 1622 Massacre killed a quarter of the colonists in Tsenacomoco (350-400). Another 400 would die in the following year as food became increasingly scarce. One of the retaliatory tactics of the English was to burn Native crops and villages. Guerrilla warfare raged on and off for the next 10 years. Opechancanough sued for peace in 1632, citing starvation among the Powhatan. Hostilities officially ended, but Anglo-Native relations were much more tense and micromanaged afterward. Most colonists were forbidden from trading or socializing with the Natives. All communication was to be handled by the governing council and their agents. Native people were required to carry an official pass to travel through English territory.

In 1644, the now elderly Opechancanough launched another concerted offensive against English settlements. Though they inflicted more casualties than in 1622, there were so many more English colonists by this time that it had less of an impact. The fighting went on for a year until the War Werowance himself was captured and brought to Jamestown to be imprisoned in public. He was soon shot in the back by one of his guards.

In the aftermath of this last war, The Powhatan Nation began to collapse. Famine and disease hastened the process as its member tribes struggled to adapt to a new reality. Some tribes died out altogether, their surviving members seeking refuge with neighbors. Some allied with the English, some maintained hostilities, but eventually all were subjugated to English rule.

Thomas Rolfe, Matoaka’s son, returned to Tsenacomoco as a teenager in 1635 to take up his father’s lands. He requested permission to visit his Powhatan relatives, including Opechancanough. It is unknown if any such meeting took place. Ultimately, Thomas chose the side of the British. It was the only world he truly knew, and by this time the world of his mother’s people had suffered drastic decline. Thomas was assigned to man and lead Fort James in the Chickahominy territory and fought against various Native tribes. By 1646 he held the rank of lieutenant and was rewarded with more lands surrounding the fort that he spent his life cultivating. He married Jane Poythress and had several children, many who would count among the colony’s future elite. The circumstances of his death are unknown.

The history of the English and the peoples of Tsenacomoco is one of scattered, broken sources, myths, and distortions. It is very much like the history of most colonial encounters. Regardless of the smaller players' intentions and actions, the larger powers behind the colonists were attempting to administer a project of wealth creation that depended on appropriating the land and labor of others. While officially forbidding violence against the Native peoples, they explicitly instructed their colonial agents to aggressively negotiate the Natives’ land from them, make their political leaders vassals of their own monarchs, and subject them to unequal trade and labor relations. The idea that these programs would be implemented without resulting in violence was ludicrous. Once the Powhatan had attacked the English in their homes, outright warfare was authorized and the security of Native people throughout the region, regardless of affiliation, was critically jeopardized.

Next week, we’ll conclude Matoaka’s Story with a look at the legacy and memory of this most famous Powhatan woman.

Sources:

22nd March 1622- History Pod

Primary Source: De Bry's "A weroan or great Lorde of Virginia"- Jamestown/Yorktown Foundation

Weroansquas and Four Centuries of Female Powhatan Leaders- Jamestown/Yorktown Foundation

Virginia Company- Virginia Encyclopedia