Pocahontas’ real name was Matoaka (Mat-oh-ah-ka). She was the daughter of Wahunsenaca (Wah-hoon-sen’-ah-ca), the leader of a nation of indigenous Virginia tribes that the English came to call the Powhatan Confederacy or Powhatan Chieftainship.

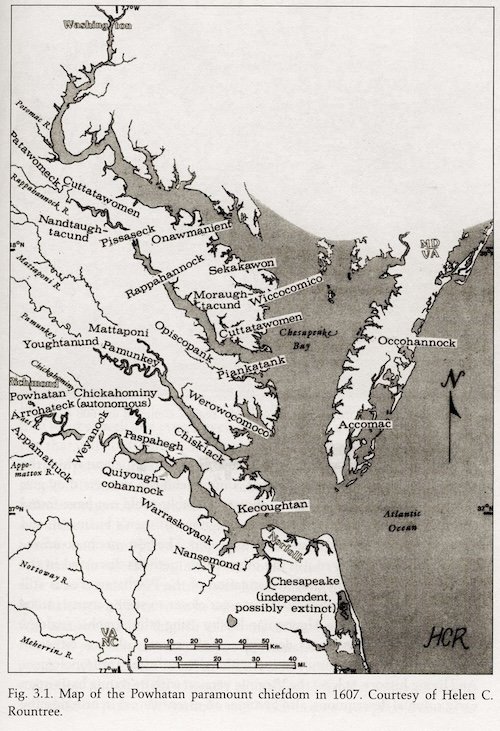

This alliance consisted of some 30 tribes. Each had a leader known as a werowance, who in turn pledged loyalty to the Paramount Werowance or Mamauatonick. Wahunsenaca was a young man when he inherited the leadership of the nation. It then consisted of 6 tribes: the Powhatan, the Pamunkey, the Mattaponi, the Appamattuck, the Arrohateck, and the Youghtanund. Over the course of his life, Wahunseneca, a Pumunkey, expanded the Powhatan, through war and diplomacy, to over 30 tribes throughout eastern Virginia. Most scholars argue that Wahunseneca exercised ultimate authority over all his tributary tribes, making it more akin to an empire, than an alliance.

Little is known for certain about how Wahunseneca brought most of the Powhatan tribes under his rule, but some of the last, incorporated shortly before the arrival of the Jamestown colonists, were through warfare. He ordered the annihilation of the nearby Chesapeake tribe soon after making contact with the English.

However, the traditional portrait of Powhatan as a fearsome chieftain concerned only with conquest may be overblown. The Mattaponi Oral History recorded that Wahunseneca ruled more through diplomacy, unlike his brother Opechancanough (O-pee-ken’-can-oo) who was considered a war leader. The Powhatan were far from the only tribal nation seeking to grow its network, there were others to the north, west, and south that they frequently came into conflict with. As the Paramount Werowance, Wahunseneca was responsible for organizing the defense of his country, as well as redistributing the wealth he collected as tribute, throughout it. These benefits of belonging to the Powhatan Nation, maintained through judicious leadership, likely brought many tribes into it voluntarily.

Political and military leaders like Wahunseneca and Opechancanough were not the only type of leadership within Powhatan society. There were also “priests'' known as quiakros (kē-ah-krōs) that organized and taught the many cultural protocols that guided life within the Powhatan country they called Tsenacomoco (Sen-ah-cō-mō-cō). Ceremonies for war, agriculture, courtship, etc., were all necessary to maintain the favor of Ahone (the creator) and other deities. Like many indigenous societies, Powhatan religious beliefs were not usually distinct from the other parts of everyday life, such as work and war. In addition to religious knowledge, quiakros also maintained knowledge about labor, politics, and wealth, making them invaluable councilors to wereowances.

Wahunseneca married a woman from every tribe within the nation, bearing children with them in order to foster kinship and unity. These wives would live with him temporarily before returning to their home villages where they were free to marry again. In this way Matoaka had many siblings throughout the Powhatan Nation. According to the Mattaponi Oral history, Matoaka’s mother, Pocahontas, married Wahunseneca for love, rather than to cement political kinship.

Matoaka’s mother died giving birth to her. Her older sister, Mattachana, cared for her for much of her life. Her testimony informed much of the Mattaponi Oral History regarding Matoaka. She lived with Mataoka in Henrico where she was a prisoner, and later the wife of John Rolfe, and also accompanied her to London in 1616. Mattachanna’s husband, Uttamattamakin was a quiakro and councilor to Wahunseneca.

There has always been confusion about Pocahontas’ other names. The Mattaponi Oral History claims that at birth, she was named Matoaka, which means “flower between two streams.” Matoaka has been recorded as revealing her birth name to English people both immediately before her baptism, and to a painter when she sat for a portrait in London. A few of the older primary resources mention that Pocahontas was a nickname, and that her proper name was Amonute. This is sometimes presented as her birth name, and sometimes as a separate name; it is unclear to me if some sources are indicating 3 names or if Amonute is a different version of Matoaka. The Mattaponi Oral History does not mention any other names besides Matoaka and Pocahontas.

She is believed to have been between 10-12 in 1607 when the first colonists arrived in Jamestown. The several eye-witness accounts of her in these early years all describe her as naked, indicating a prepubescent child. Powhatan women were noted by early writers as wearing “aprons” about their waists and did not wish to be seen without them. There are several accounts of the young daughter of the Powhatan “chief” playing with English children in Jamestown, showing them how to do cartwheels. These are the years she would have known John Smith, making the possibility of a romance, or her presence at the ritual that inducted him into the Powhatan Nation, highly unlikely.

After Smith departed and tensions between the Powhatan and the English rose, Matoaka did come of age, and married a Patawomeck (pat-ah-ow-mek) warrior named Kakoum. The Mattaponi Oral History recorded that they had a son and lived together in a Patawomeck village north of her father’s village, Werowocomoco (where-ō-wō-cō-mō-cō).

Sources:

Eastern Algonquian Social Structure in the 17th Centrury- Jamestown/Yorktown Museums

Paramount Chief Powhatan- Jamestown/Yorktown Museums

Werowocomoco: A Powhatan Place of Power- National Park Service