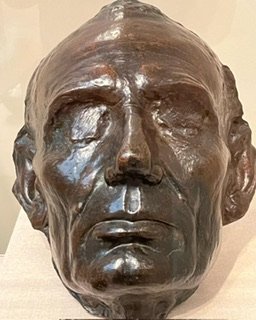

John Wilkes Booth. Black & Case of Boston back mark. Date unknown. Public Domain.

John Wilkes Booth was born in Maryland in 1838. His father, Junius Brutus Booth, was an English actor who immigrated to the US in 1821 with his mistress and John’s mother, Mary Ann Holmes.

Booth began acting in his youth and went on to have a successful career. Critics often remarked on his good looks and energetic performances. After the election of Abraham Lincoln, southern states began seceding from the US. Booth earned praise from some quarters, and scorn from others for his passionate support of the Confederacy.

As the war turned in the Union’s favor, Booth began plotting with a small group of sympathizers to kidnap the president. Their attempt was thwarted by a last minute change to Lincoln’s travel plans. Soon after Booth learned that the Lincolns would be attending a performance of “Our American Cousin,” at Ford’s Theatre, a venue he had performed at and knew well.

On April 14, Booth slipped into the president’s box and shot him in the back of the head. He leapt from the box down to the stage, injuring his leg in the process, and cried out “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” a famous line from the play Julius Caesar meaning “thus always to tyrants.” He escaped DC with one of his co-conspirators, David Herold. The 2 evaded Union soldiers for 12 days before being cornered in a barn near Port Royal, Virginia on April 26, 1865.

Herold surrendered, but Booth refused, demanding that the soldiers move back and allow him to come out and fight with his knife and pistol. Eventually, Sergeant Thomas Corbett fired into the barn hitting Booth in the neck. Corbett claimed he shot after Booth raised his pistol to fire on them, but several other soldiers disputed this claim. Booth died several hours later on the porch of a nearby house.

Sources:

Material Evidence: John Wilkes Booth- Ford’s Theatre

Who was John Wilkes Booth before he became Lincoln’s Assassin?- NPR